19 Dec From Brooklyn to Boynton Beach: A pioneering performer looks back

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Thanks to my father’s late-life nostalgia, last summer my family reconnected with a woman we’d known back in Brooklyn decades ago who’d gone on to live a remarkable life. Her name is Lynn Lavner, and it turns out, she’d been living under 10 miles away from my parents’ place in south Florida for years. It also turns out that in the decades since we’d seen her, she’d become a pioneering crusader in the movement for gay civil rights.

Though my parents had been full-time residents of Florida since 1988, in the last years of my dad’s life his mind got stuck on his happiest time, during the late 1970s in Brooklyn, New York.

That’s when a small crew of people were running around various venues in the New York area, performing a musical written he’d co-written with his dear friend, Chuck Reichenthal called Hit Tunes from Flop Shows.

Lavner had served as the first piano player for the show. At the time she also happened to be a teacher at Ditmas Junior High School in Brooklyn, a school both my brother and I attended.

Lavner had served as the first piano player for the show. At the time she also happened to be a teacher at Ditmas Junior High School in Brooklyn, a school both my brother and I attended.

One day last August, my father demanded to know with some urgency to know where Lynn Lavner could be found. I remembered her name, and wondered, too, what had become of her.

Wanting to be a good daughter, I took out my laptop and started searching. It took less than a New York minute to determine that she lived nearby.

My father demanded her phone number, and forgetting the social nicety of not calling until a certain hour, dialed the phone. She answered, and he identified himself, as if he’d just talked to her yesterday. And as is the case with most old friends, it was almost as if they had—like she’d been waiting for him to call all morning.

Suddenly, she and and Ardis, her partner of 41 years, were expected for lunch two days hence. (If they and we hadn’t had appointments the next day, they would have likely come over then.)

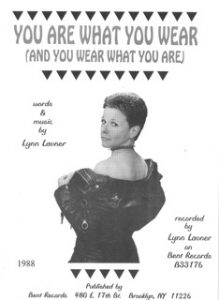

Since we’d lost touch, Lavner had left the New York City Public School System, and become a major figure on the LGBT performance circuit. From the gay and lesbian clubs in New York, she’d gone on tour around the world as “America’s most politically incorrect performer,” hosting at women’s festivals and other venues that were boldly being staged to rally for what then seemed unattainable: Gay civil rights. She’d become the public voice of the crusade for gay equal rights at a critical, early time in the movement. Ardis traveled the world with her as her manager.

Since we’d lost touch, Lavner had left the New York City Public School System, and become a major figure on the LGBT performance circuit. From the gay and lesbian clubs in New York, she’d gone on tour around the world as “America’s most politically incorrect performer,” hosting at women’s festivals and other venues that were boldly being staged to rally for what then seemed unattainable: Gay civil rights. She’d become the public voice of the crusade for gay equal rights at a critical, early time in the movement. Ardis traveled the world with her as her manager.

The friendship between these two couples rekindled quickly. Various lunch dates ensued. In October, with my parents about to mark their 60thwedding anniversary, it was Lynn and Ardis invited them over for a special dinner. Plans were discussed for an upcoming party, at which Lynn would play piano and my dad would sing. They sang a duet as practice: “The Wedding Song,” which my father had sung as his parents’ 50thanniversary.

The rest of us never got to hear Napoli/Lavner perform. My father suffered a heart attack the next day, and he died not long after. During the excruciating period of waiting, I comforted myself by visiting with Lynn—and asking her about her career. What you’ll hear in this piece are her recollections about life on the road as performer during a pivotal time in our history.

My father gave us all an amazing gift at the end of his life: new, old friends. And I’m honored to help tell the story of a woman who helped give voice to a movement. I hope you’ll give a listen to her words and her music. (Thanks to Charlton Thorp for mixing the piece so beautifully.)